HPC Session 04 OpenMP (3/3)

OpenMP(3/3)

atomic operations

criticaldirectives protect code blocks from parallel accessatomicdirectives protect individual variables from parallel access

Recall the critical resolution of the inner product of a & b:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

double result = 0.0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

double myResult = 0.0;

#pragma omp for

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

myResult += a[i] * b[i];

}

#pragma omp critical

result += myResult;

}

Using an atomic update:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

double result = 0.0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

double myResult = 0.0;

#pragma omp for

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

myResult += a[i] * b[i];

}

#pragma omp atomic <----

result += myResult;

}

- The atomic clause tells the compiler that on the next line,

- Thread acquires the lock

- Thread updates the result

- Thread releases the lock

- If updating different elements, i.e.

x[k], then atomic will letx[k]andx[l]update simultaneously when k 6= l (critical does not!).

Concept of building block

- Content

- Introduce term atomic

- Introduce atomic operator syntax

- Study (potential) impact of atomic feature

- Expected Learning Outcomes

- The student knows of atomics in OpenMP

- The student can identify atomics in given codes

- The student can program with atomics

Thread communication—repeated

We distinguish two different communication types:

- Communication through the join

- Communication inside the BSP part (not “academic” BSP)

Critical section: Part or code that is ran by at most one thread at a time.

Reduction: Join variant, where all the threads reduce a value in to one single value.

- Reduction maps a vector of $(x_0, x_1, x_2, x_3, . . . ,x_{p-1})$ onto one value *x, i.e. we have an all-to-one data flow

- Inter-thread communication realised by data exchange through shared memory

- Fork can be read as one-to-all information propagation (done implicitly by shared memory)

Collective operations

Collective operation: A collective operation is an operation that involves multiple cores/threads.

- Any synchronisation is a collective operation

- BSP/OpenMP implicitly synchronises threads, i.e. we have used synchronisation

- Synchronisation however does not compute any value

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

double result = 0.0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

double myResult = 0.0;

#pragma omp for

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

myResult += a[i] * b[i];

}

#pragma omp barrier

}

- The above fragment synchronises all threads

- This type is a special type of a collective operation

- Barriers are implicitly inserted by BSP programming model

换一种

- Challenge: Synchronisation does not compute any value

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

double result = 0.0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

double myResult = 0.0;

#pragma omp for

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

myResult += a[i] * b[i];

}

#pragma omp critical

result += myResult;

}

- The above fragment mimics an all-to-one operation (all threads aggregate their data in the manager threads result variable)

- This type is called reduction which is a special type of a collective operation

- OpenMP provides a special clause for this

Reduction operator

- We have been looking at various ways to combine the results from parallel computation on a group of

- This is a classic parallel computing communication pattern – think about computing the norm of a vector!

⇒ This pattern is called a reduction

- Thread communication relies on shared memory

- Writing this communication manually is tedious – OpenMP provides a clause:

1

#pragma omp parallel for reduction([operator]:[variable])

- Some restrictions for reduction:

- operator must be binary associative; e.g., a ⇥ (b ⇥ c) ⌘ (a ⇥ b) ⇥ c

- operator must have an identity value for initialisation – e.g., 1 for ⇥

- variable must be built-in type – e.g., int or double

- variable must not appear in (other) data clauses – reduction takes primacy

Reduction pragma

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

double result = 0;

#[1] #pragma omp parallel for reduction(*:result)

#[2] #pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:result)

#[3] #pragma omp parallel for private(result) reduction(+:result)

#[4] #pragma omp parallel for firstprivate(result) reduction(*:result) for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

result += a[i] * b[i];

}

Which pragma line is correct?

Reduction keyword is parameterised with (commutative) operation (+,-,*,&, ,. . . ) - Reduction works solely for scalars.

- Keyword makes scalar private first but then merges the threads’ scalars.

- Keyword initialises private copy with identity w.r.t. the operator.

Performance study

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

double result = 0.0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

double myResult = 0.0;

#pragma omp for

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

myResult += a[i] * b[i];

}

#pragma omp critical

result += myResult;

}

1

2

3

4

5

double result = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:result)

for( int i=0; i<size; i++ ) {

result += a[i] * b[i];

}

Concept of building block

- Content

- Introduce term collective

- Introduce reduction syntax

- Study (potential) impact of reduction feature

- Expected Learning Outcomes

- The student knows of reductions in OpenMP and their variants

- The student can identify reductions in given codes

- The student can program with reductions

My work is more varied than iterating over a loop…

Sometimes we will have a large set of loosely-related subproblems with relatively shallow dependencies.

Or sometimes we will have multiple computations which are independent, but need to be combined in some way for another computation.

The archetypal parallelization method for this type of problem is tasking.

If not all threads shall do the same

A manual task implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#pragma omp parallel for schedule(static:1)

for (int i=0; i<2; i++) {

if (i==0) {

foo();

}

else {

bar();

}

}

Shortcomings:

- Syntactic overhead

- If bar depends at one point on data from foo, code deadlocks if ran serial

- Not a real task system, as two tasks are synchronised at end of loop

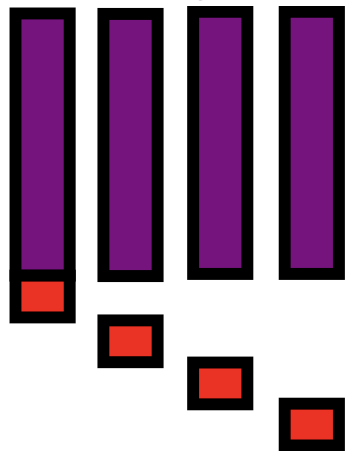

Tasks in OpenMP 3.0

Introduce new task keyword:

1

#pragma omp taskParallel regions sets up queues:

1

#pragma omp parallelAll tasks that are parallel to each other befill this queue

Before OpenMP 3.0 there used to be a

1

#pragma omp sectioncommand. The standard does not specify, whether sections can be stolen.

Tasks may spawn additional tasks – classic example is recursive algorithms

Task example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp single

{

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A\n" );

printf( "we stop Task A now\n" );

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A.1\n" ); }

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A.2\n" );

}

#pragma omp taskwait

printf( "resume Task A\n" );

}

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task B\n" );

}

#pragma omp taskwait

#pragma omp task

printf( "Task A and B now have finished\n" );

}

}

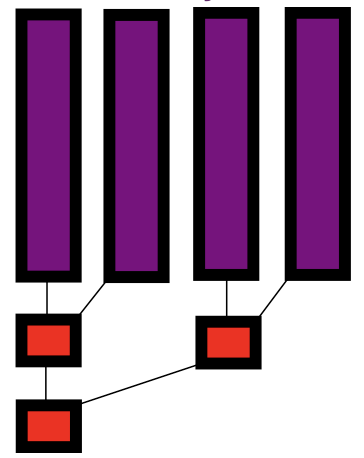

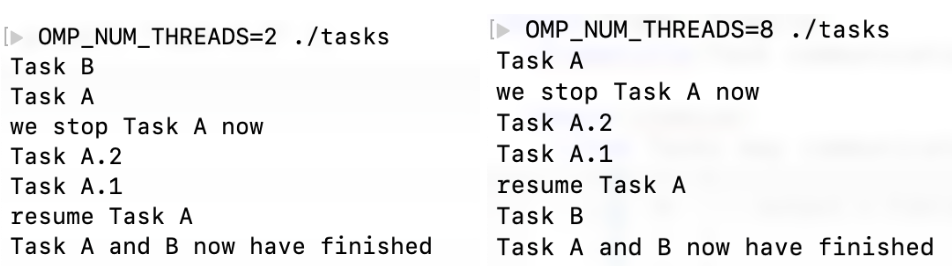

- Which

printfcall prints first?

Experiment

- Either ‘Task A’ or ‘Task B’ lines print first

- Task A stop line always follows ‘Task A’

- ‘Task A.1’ and ‘Task A.2’ should precede ‘resume Task A’

- ‘Task A and B have finished’ is always last

Task communication

- Tasks may communicate through shared memory

- Critical sections remain available

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp single

{

#pragma omp task

foo();

#pragma omp task

bar();

}

}

Observations:

- OpenMP pragmas are ignored if we compile without OpenMP )

⇒ Code still deadlocks if bar depends on

⇒ Should work with OMP NUM THREADS=1

- There is still an implicit join where

omp parallelterminates

⇒ Task paradigm is embedded into fork-join model

Task example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp single

{

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A\n" );

printf( "we stop Task A now\n" );

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A.1\n" ); }

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task A.2\n" );

}

#pragma omp taskwait

printf( "resume Task A\n" );

}

#pragma omp task

{

printf( "Task B\n" );

}

#pragma omp taskwait

#pragma omp task

printf( "Task A and B now have finished\n" );

}

}

- Can you draw the task dependency graph? It is the “inverse” of the spawn graph!

Tasking case study: Recursive Fibonacci

Recall the Fibonacci sequence: f0 = 0, f1 = 1, fn* = *fn1 + f**n2

- Classic example of a (bad) recursive computation

- This is pedagogical, not a recommendation for task parallelism . . .

- Consider the serial implementation of fib below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int fib(int n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

int x = fib(n - 1);

int y = fib(n - 2);

return x+y;

}

int main(int argc,char* argv[]){

// ...

fib(input);

// ...

}

How would we use tasks for this . . .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

int fib(int n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

int x, y;

#pragma omp task shared(x)

x = fib(n - 1);

#pragma omp task shared(y)

y = fib(n - 2);

#pragma omp taskwait

return x+y;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]){

// ...

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp single

{

fib(input);

}

}

// ...

}

- One thread enters fib from main, spawns two initial work tasks

- Requires

taskwaitto recover intermediatex&y– not all child tasks - From

main, we only need to call the fib function once.

Concept of building block

- Content

- Introduce task parallelism

- Discuss task features compared to “real” tasking systems

- Expected Learning Outcomes

- The student can analyse OpenMP’s task concept and upcoming features

- The student can write a task-based OpenMP code