PO Lecture 2 Memory Hierarchy

作业回顾

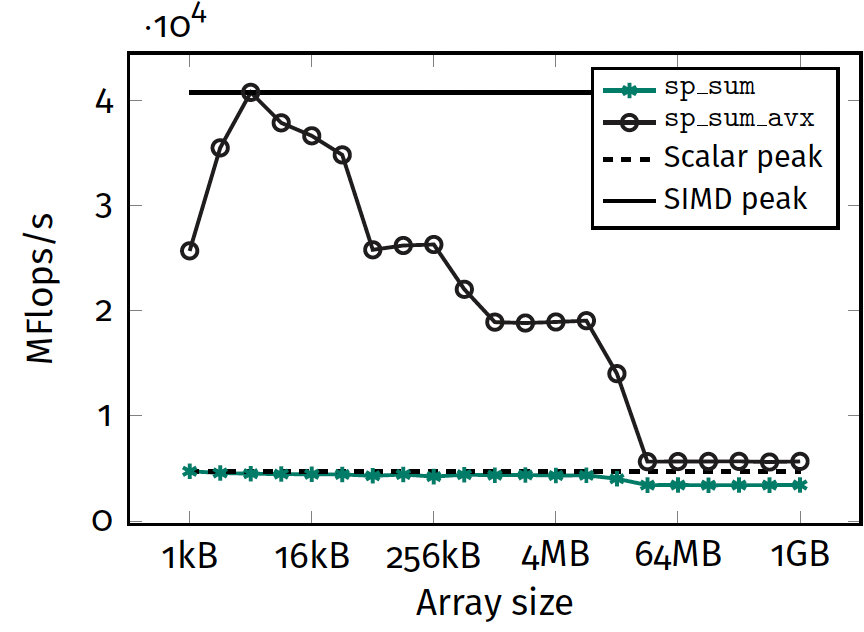

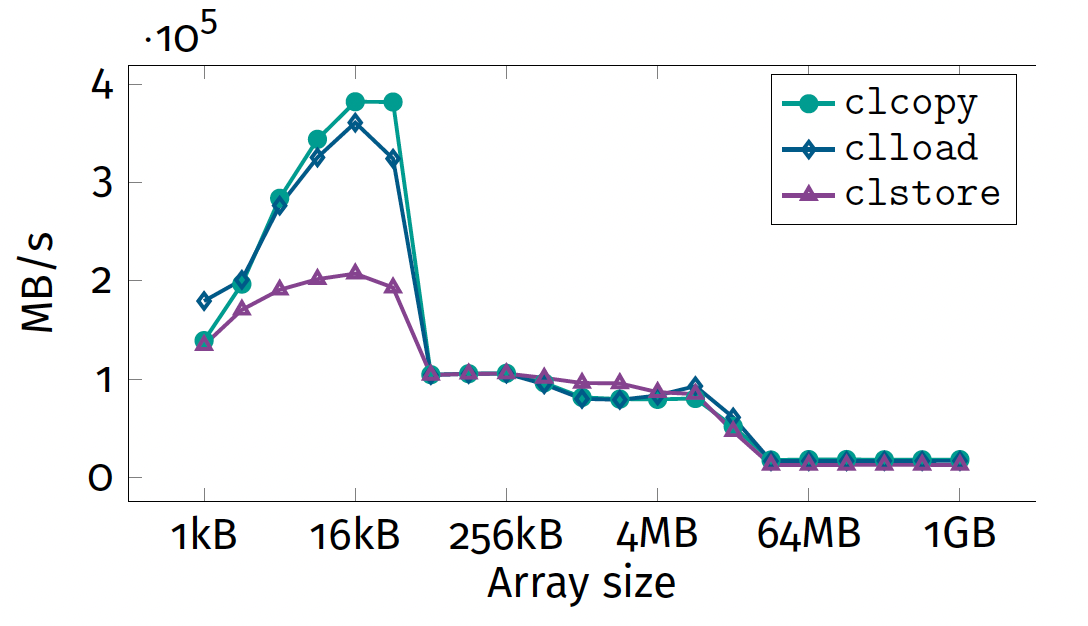

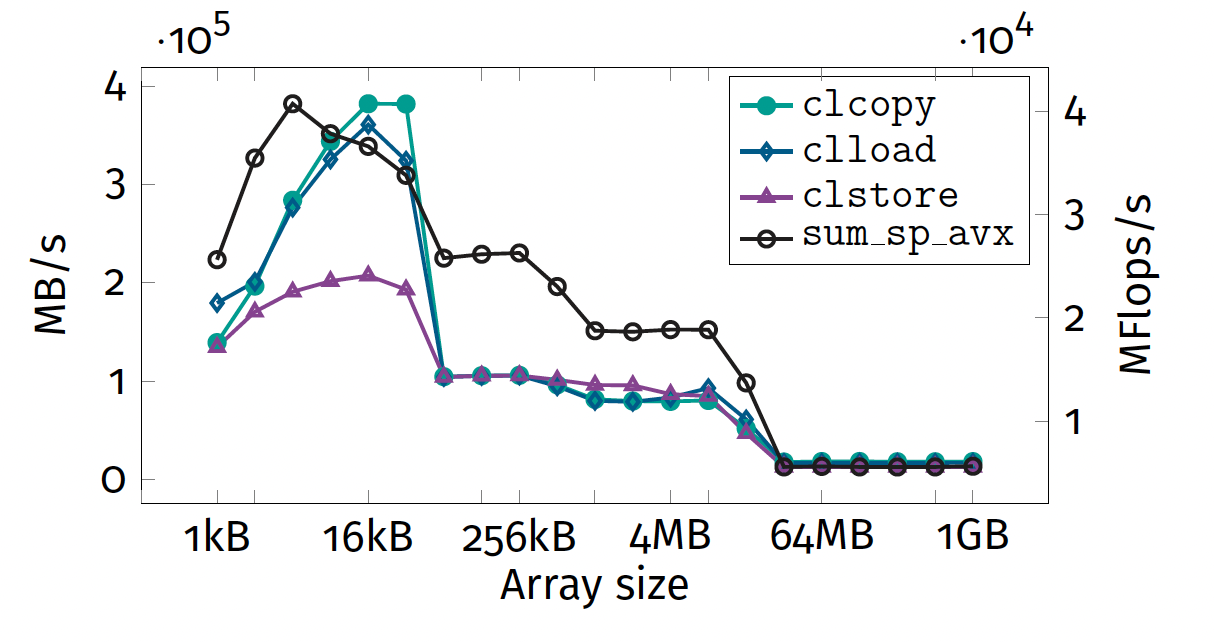

Sum reduction benchmark (Exercise 1)

- SIMD: 4 plateaus

- scalar: 3 plateaus

Performance peak

Variability This is due to CPU Boosting.

Question SIMD code does not achieve theoretical peak for all sizes. Why?

Hardware bottlenecks

- Cannot be instruction throughput.

- Memory bandwidth decreases with vector siz

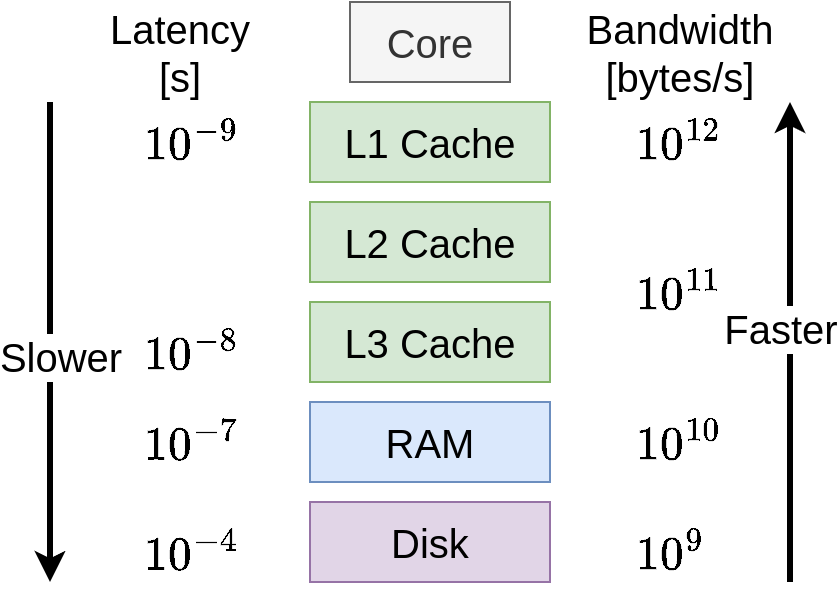

Memory Hierarchy

Two types of memory:

▶ small and fast

▶ large and slow

Large and fast is impossible:

⇒ physics gets in the way.

Optimisation: refactor algorithms to keep data in fast memory.

Check Colin Scott’s page for more detail on latencies.

Cache memory: overview

Features

- Hierarchy of small, fast memory.

- Keep a copy of frequently used data for faster access.

Issues

- Frequently accessed data not known a priori.

- Only heuristics are possible → principle of locality.

Principle of locality

- Frequently accessed data often unknown before execution

- In practice, most programs exhibit locality of data access.

- Optimised algorithms attempt to exploit this locality.

Temporal locality If I access data at some memory address, it is likely that I will do so again “soon”.

Spatial locality If I access data at some memory address, it is likely that I will access neighbouring addresses.

Temporal locality

On first access to a new address, the data is:

- loaded from main memory to registers

- stored in cache

Temporal locality

On first access to a new address, the data is:

- loaded from main memory to registers

- stored in cache

Trade-off solution:

- Small performance penalty for first access (storing is not free)

- Subsequent accesses use cached copy and are much faster.

Spatial locality

On first access to a new address, the data is:

- loaded from main memory to registers

- stored in cache

- neighbouring addressed are also stored in cache

Trade-off solution:

- Large performance penalty for first access

- Subsequent accesses to neighbouring data will be fast

Example: sum reduction

1

2

3

float s[16] = 0;

for (i = 0; i < N; i++)

s[i%16] += a[i];

- Temporal locality

- 16 entries of

sare accessed repeatedly - Makes sense to keep all of

sin cache

- 16 entries of

- Spatial locality

- Contiguous entries of

aare accessed - When loading

a[i]it makes sense to loada[i+1]too.

- Contiguous entries of

Designing a cache

Important questions

- When we load data into the cache, where do we put it?

- If we have an address, how do determine if it is in the cache?

- What do we do when the cache becomes full?

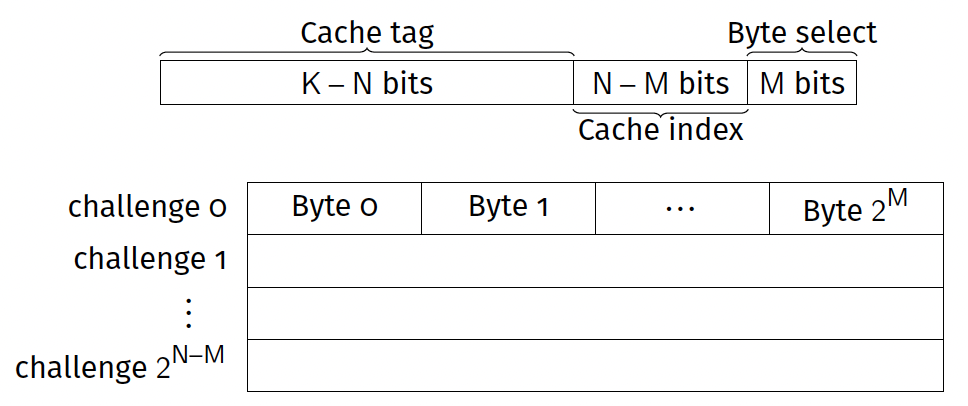

- Each datum uniquely referenced by its K-bit address

- Need to turn this large memory address into a cache location

- K is typically large ($2^{32} / 2^{64}$ addresses)

Direct mapped cache

- Cache can store $2^N$ bytes

- Divided into challenges (or cache lines) each of $2^M$ bytes

- Each address references one byte

- Use N bits of address to select which slot in the cache to use

Simplest solution: injection from RAM to cache

Direct mapped caches: indexing

- Byte select: Use lowest M bits to select correct byte in challenge.

- Cache index: Use next N – M bits to select correct challenge.

- Cache tag: Use remaining K – N bits as a key.

Choice of cache line size

- Data is loaded one cache line at a time

- Immediately exploits spatial locality

- Larger cache lines are not always better

- Almost all modern CPUs use 64-byte size

Rule of thumb Cache-friendly algorithms work on cache line-sized chunks of data.

Direct mapped caches: eviction

- Conflict: two addresses have the same low bit pattern

- Resolution: newest loaded address wins.

- This is a least recently used (LRU) eviction policy.

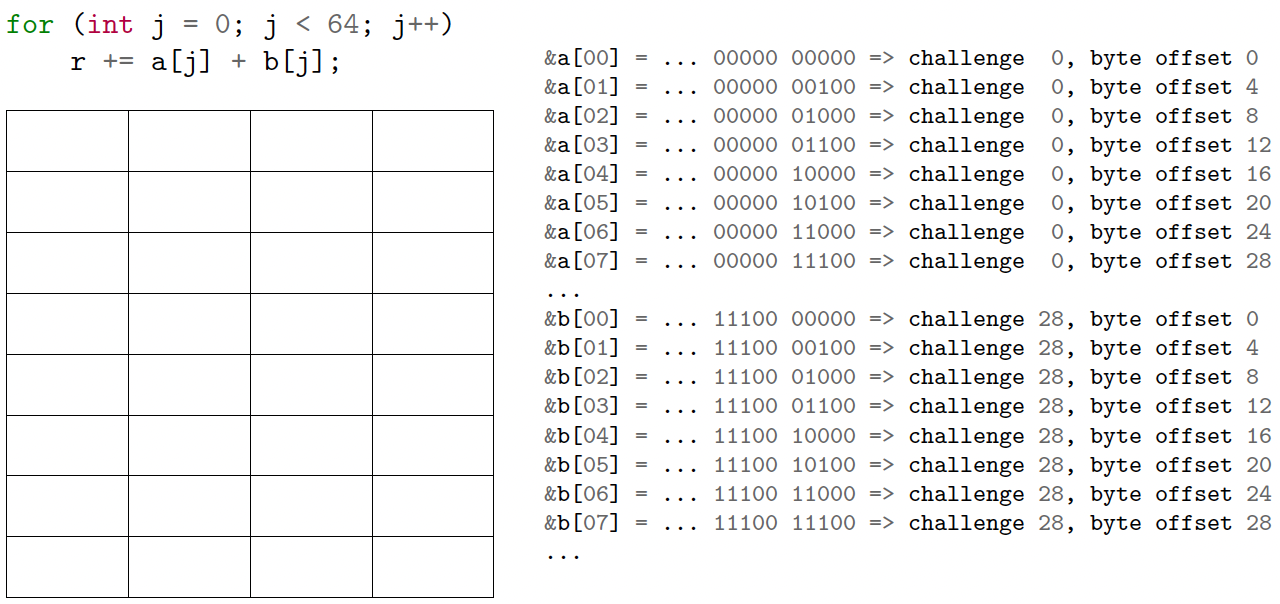

What can go wrong?

1

2

3

4

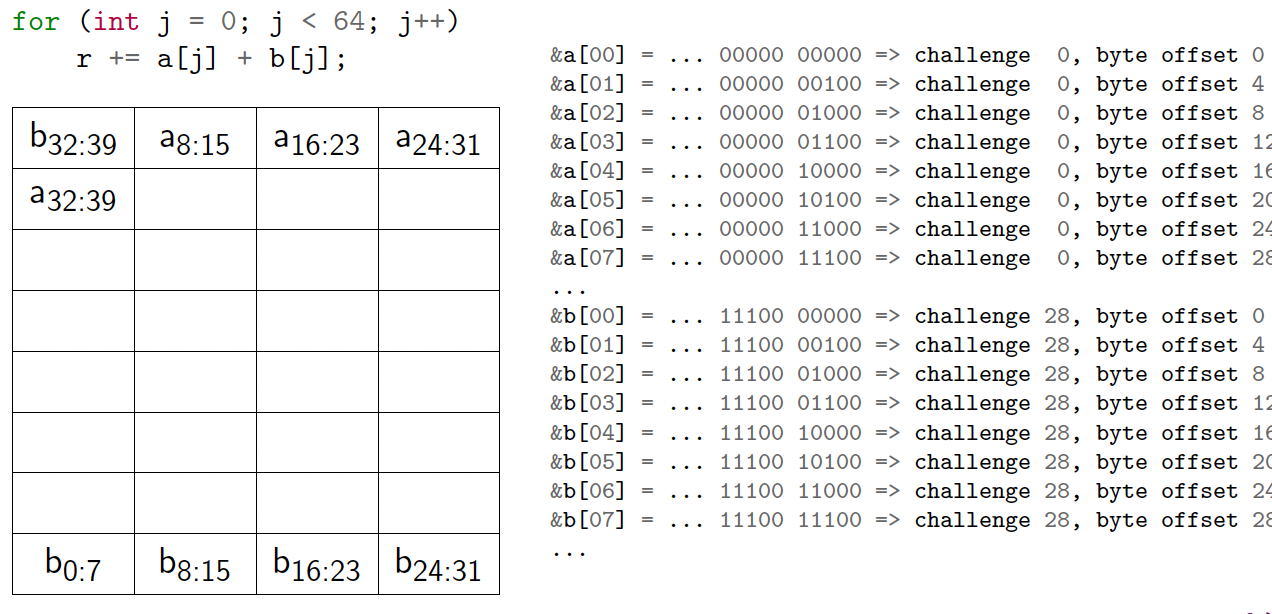

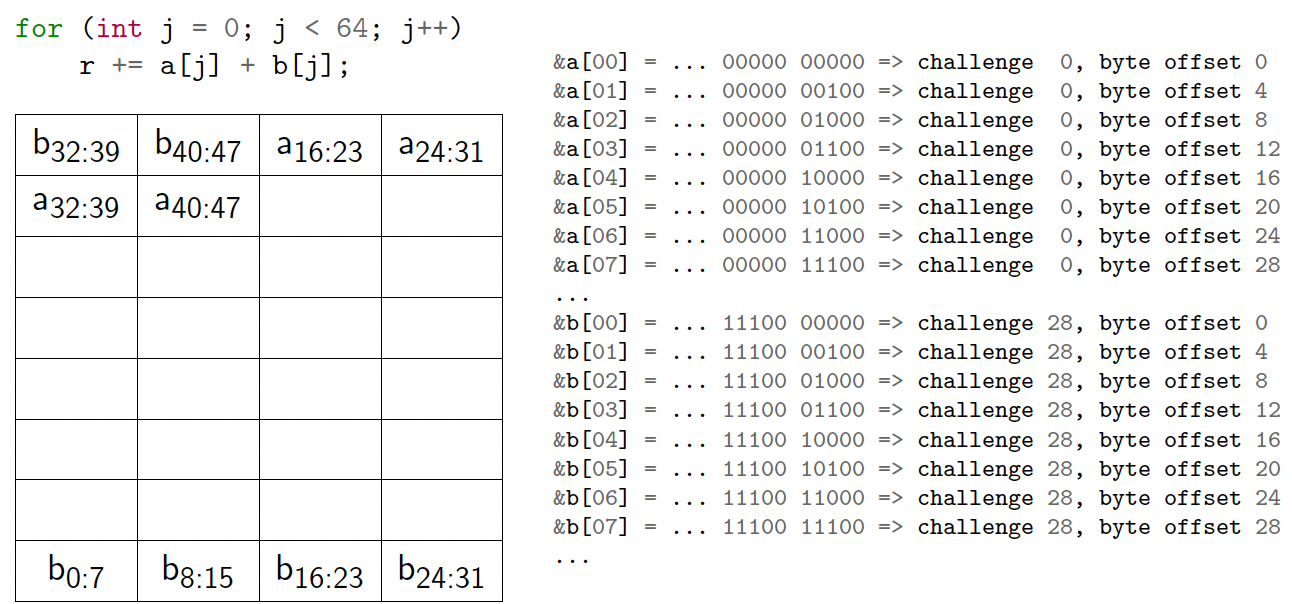

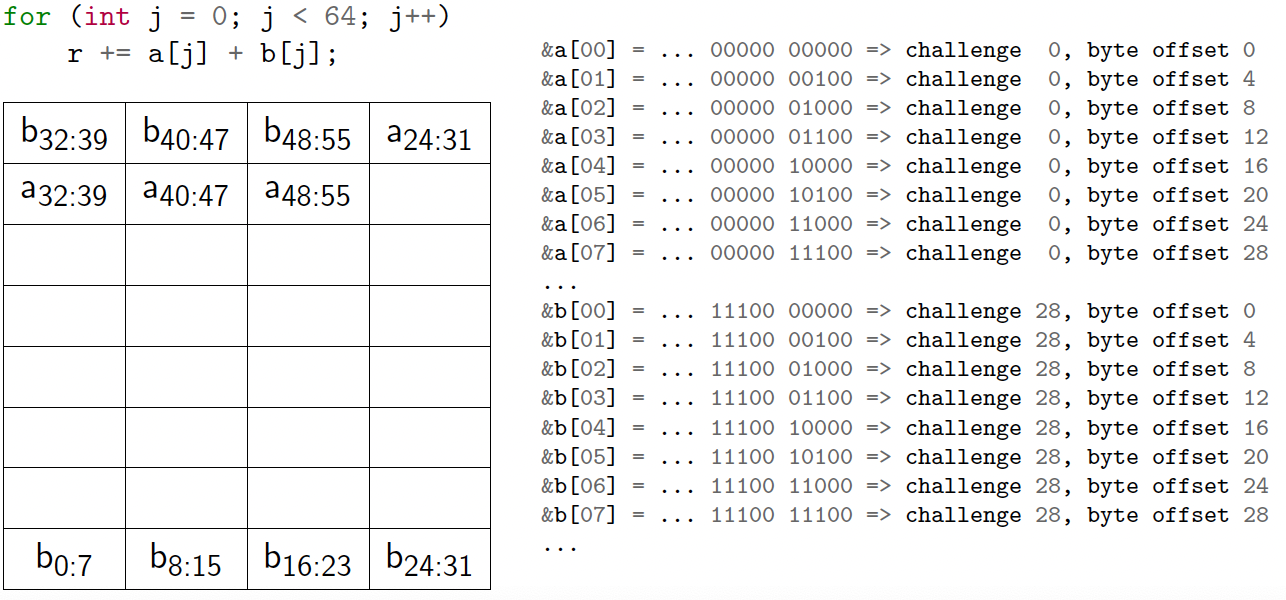

int a[64], b[64], r = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < 64; j++)

r += a[j] + b[j];

- 1KB cache

- 32-byte challenge size

- So N = 10, M = 5

- 32 challenges in the cache

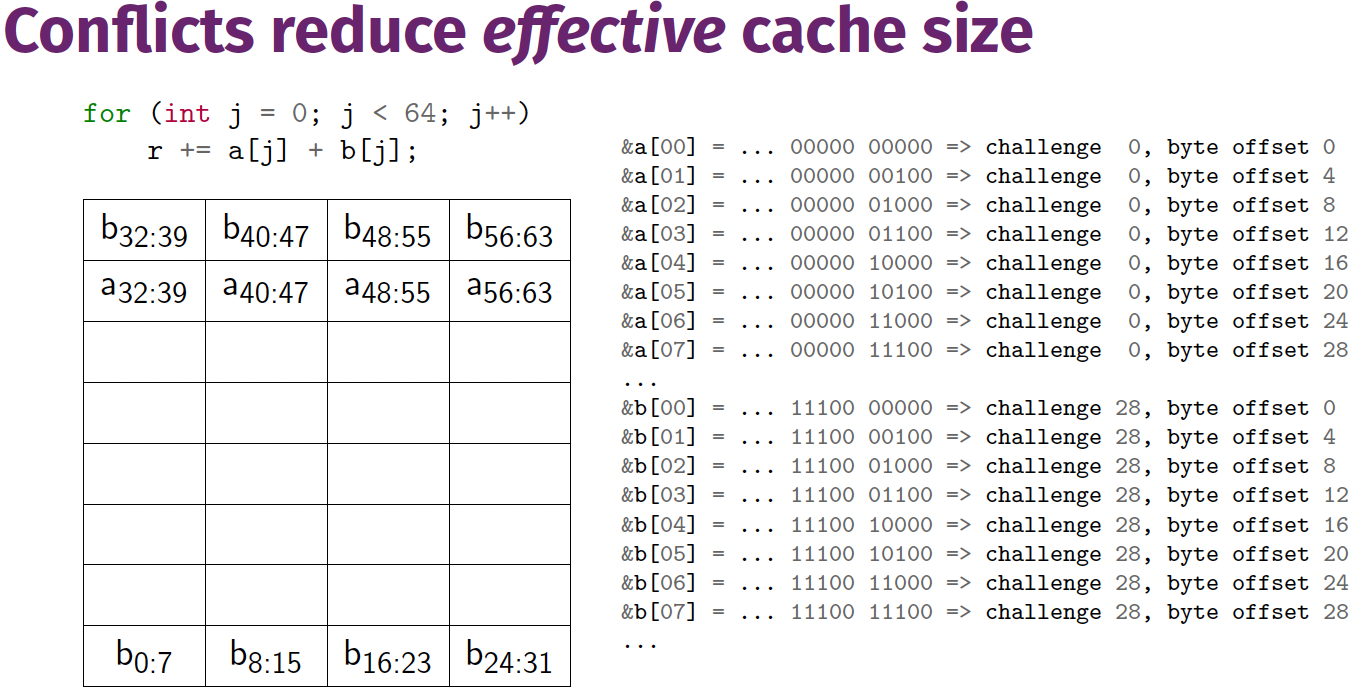

Conflicts reduce effective cache size

Cache thrashing

What can go wrong?

1

2

3

4

int A[64], B[64], r = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

for (int j = 0; j < 64; j++)

r += A[j] + B[j];

- 1KB cache

- 32 byte challenge size

So N = 10, M = 5. 32 challenges in the cache.

- We need $2 \cdot 64 \cdot 4 = 512$ bytes to store A and B in cache.

- This only requires 16 challenges, so our cache is large enough.

- If low bits of addresses match, same cache lines are mapped.

- In the worst case, every load of $B[j]$ evicts $A[j]$, and vice versa.

Cache associativity

- Direct mapped

- Each RAM challenge maps to exactly one cache line.

- LRU eviction policy (new data overwrite old)

- Fully associative

- Each RAM byte can map to any cache line

- Data is stored in first unused cache line

- If all lines are used, overall LRU one is replaced

- Most flexible, but also most expensive

k-way set associative cache

- k “copies” of a direct mapped cache.

- Each challenge from main memory maps to k cache lines, called sets.

- Typically use LRU eviction.

- Usual choice: N ∈ {2, 4, 8, 16}.

- Skylake has N = 8 for L1, N = 16 for L2, N = 11 for L3.

Exercises 2/3: memory bandwidth/saturation

Split into small groups

Make sure one person per group has access to Hamilton

Benchmark memory bandwidth as a function of vector size

You can use the bash script from last week.

Ask questions!